Explorations in Self Managed eLearning

FROM TEACHING & LEARNING ONLINE - NEW MODEL OF LEARNING FOR A CONNECTED WORLD, VOL 2, EDS SUTTON, B. & BASIEL, A. 2014, ROUTLEDGE.

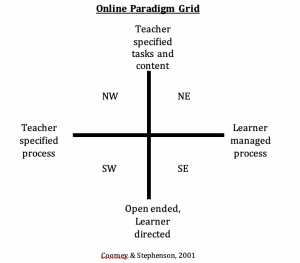

I had thought that I might call this chapter ‘Explorations in the South East’ – but that would have been, perhaps, too elliptical and mystifying. My thought about the title was influenced by the model below from Coomey and Stephenson (2001).

Put simply, they postulate two dimensions in relation to learning – one about who decides the process (shown as the horizontal axis) and one about who decides the content and tasks (shown as the vertical axis). The juxtaposition is of teacher controlled versus learner controlled. There is more to their work than my simplified version here, but what I want to do is to get into the practicalities of what it looks like to work in the South East quadrant. As the authors identified, most of e-learning has been in the North West quadrant. It is still about teachers (or others in authority) deciding both what to learn and how to learn it. Just changing the process from classroom controlled learning to online instructor controlled misses the point about what the potential shift is when we think differently about the liberatory potential of elearning and the use of technology.

In this chapter I will offer models that underpin practice, but my aim is mostly to show that working in the South East quadrant is perfectly feasible. I will do this by introducing some real examples of practice. Why we should work in this way is explored more fully in many other texts. The work of my colleagues and I in developing Self Managed Learning as a specific approach is covered in, for example, Cunningham (1999) and Cunningham et al (2000). These texts provide both theoretical justifications for the approach as well as research evidence of practice in organisations.

In what follows I will go through examples of experiences along the journey I have taken in exploring a more self managed approach to elearning. I have organised this chronologically to make some sense of how things have changed over time. In various cases I will show how the experience links to theory.

In summary the chapter follows the following path:

- A brief critique of other modes of elearning and of the mis-use of technology.

- An outline of an early experience of computer conferencing

- The distinction between Dynamic and Static elearning

- A practical example of an online Master’s degree using a self managed mode

- A model identifying what is needed to create an effective elearning programme – using the Master’s degree as an exemplar.

- Self Managed Learning College as an example of elearning practice with young people.

- Digital Education Brighton as a collaborative project

- A brief conclusion

A brief critique of other modes of elearning and of the mis-use of technology

Through to the mid-1980s I had been somewhat disillusioned with the use of technology to support learning. The translation of rigid teaching material from the teacher-controlled classroom into rigid material in machines – initially devices such teaching machines then computers – did not seem to herald much progress. Other technology uses such as film and OHPs were still teacher led modes of instruction. They had their uses but were no breakthrough in learning methodology.

This strand of the use of technology has continued in the shape of PowerPoint, highly standardised elearning material and so on. When I am told that we all know this and that the world has moved on I am inclined to disagree. I am not ‘flogging a dead horse’ – I am with Koestler (1964) who posited the notion of a society for the preservation of dead horses. Most elearning and educational technology in general continues in the same vein as the past and it is not flogging a dead horse to continue its critique.

We also need to address the continuing problem of teacher control of resources. For instance I was told that when interactive whiteboards were created the idea was for a horizontal surface that learners could use for their learning – with a group around the surface. What happened was teachers made certain that the device was hung vertically behind them in a traditional classroom layout and that students accessed it via permission from the teacher. This way of thinking needs to change.

An outline of an early experience of computer conferencing

In the mid-1980s I was keen to co-operate with other researchers in different parts of the UK. This was before the age of the Web and email so we either had to meet up or write to each other or phone. There were no other choices available. The phone mode was very one-to-one and meeting up was difficult, time consuming and costly. Sending written work to each other was time consuming and did not allow for interaction.

One of the group, David O’Connell (see O’Connell, 1994), introduced the rest of us to computer conferencing. We did this via JANET (the Joint Academic Network that linked various UK universities via a server in Lancaster University). Given that this was before the Web was available, the software was somewhat clunky, but the fact that we could share ideas and collaborate via the computer was an eye-opener. We were able to manage our own learning. We were in control via a process that allowed us to do what we wanted with it.

The distinction between Dynamic and Static elearning

This facility is now common place via the Web but at the time it showed possibilities for empowered learning that was not controlled by the teacher or by a curriculum. The distinction in learning modes that I want to draw is between

DYNAMIC MODES

and

STATIC MODES.

Computer conferencing is an example of a Dynamic Mode. It allows for interaction and flow that goes where the users want to take it. Learning is more social and more open. It is managed by the learners. Static Modes are characterised by the static provision of unalterable material or material controlled by another (for example a teacher). Such material may also be sequenced in a way that cannot be altered, as in much elearning. Indeed a text book that you can dip into and flick through can be less static than sequenced elearning material that controls the way you have to progress through the material.

Rose Luckin’s (2010) book entitled ‘Re-designing Learning Contexts – Technology-rich, learner-centred ecologies’ is one I will return to later as her stance is linked to a relevant case study that she researched. Here I will quote from her introduction:

“I worked alongside Lydia Plowman who drew my attention to the concept of ‘Lines of Desire’, a term borrowed from architecture and planning that refers to the routes that people take through open or semi-open spaces, in preference to those marked out as paths by planners……I found this concept offered an appealing metaphor as I considered how learners might be able to look around them and find out enough information about people, buildings, books, pens, technologies and other artefacts within their landscape to chart a learning trajectory that would meet their needs.”

(p. 3)

In this context the opportunity for learners to use Static Modes for their own learning trajectories makes sense. Another way of putting this is to say that if learners are in charge of their learning strategy the fact that they use Static tactics to support this does not run counter to a self managed mode (1). In our research group working at a distance the computer conferencing strategy (Dynamic) did not preclude the use of Static tactics such as reading existing literature. The key was the overall strategic approach that made a big difference in how we could work together and share our on-going research work. And the on-going research that each of us was conducting was enhanced by the strategic learning collaboration.

A practical example of an online Master’s degree using a self managed mode

The story now leaps to the mid-1990s when the internet became much more available. I was involved in the early days of an MA in Organisation Design and Effectiveness at what was then the Fielding Institute in Santa Barbara, California. Part of the basis of the degree was for participants to learn to a) work internationally (they were largely senior people in international companies) and b) use the technology. The way participants would learn both these would not be through overt teaching but through the process of the programme.

This is an example of using the power of the process curriculum – the actual way of learning – as opposed to the content curriculum of traditional education. In the traditional classroom it gave rise to the notion of the ‘hidden curriculum’. Writers identified that the hidden curriculum either encouraged dependency on the teacher or counter-dependent rebellion. The process of a teacher controlled learning environment has these effects on many learners and this undermines the ability of young people to grow up as fully autonomous human beings.

The notion of a hidden curriculum was originally articulated by Jackson (1968) and then explicitly developed by writers such as Snyder (1970) who saw the socialisation of the classroom as reducing autonomous action and having longer term negative effects. Vallance (1983) makes the case for considering the strong role of the hidden curriculum in her statement that it includes “the inculcation of values, political socialization, training in obedience and docility, the perpetuation of traditional class structure-functions that may be characterized generally as social control” (P. 10).

These, and many other writers, only saw the process of learning in educational institutions as a negative factor. However I have suggested that we can take a positive position on how, for instance, the teacher/professor works with learners and how the design of programmes can actually assist learner autonomy. If we want to develop autonomous learners then the process needs to match the aim – means and ends need to be harmonised.

In the MA programme the idea was to use the process curriculum to good effect. The process was made overt and did not therefore constitute a hidden curriculum. We were designing and implementing a process to liberate learners from the constraints of classroom learning.

We, the faculty, made it abundantly clear that we were encouraging cross-cultural learning and learning about technology as part of the process curriculum. We judged that these abilities would become crucial in an increasingly globalised world. This judgement was made on the basis of the trends occurring in the global economy and the way technology was becoming more central to people’s lives. The judgements we made at the time have been justified by developments since. For instance at the time many managers in organisations did not have their own email address – something that is unthinkable now. Similarly the work of researchers such as Hofstede (2001) and Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997) has spawned a massive literature in cross-cultural working.

In order to implement the process curriculum participants were recruited from around the world and they were linked via the internet using what is now defunct software – Alta Vista Forum. The participants met face-to-face for three days at the start of the programme to learn about each other and to learn how to use the software. (Remember this was in the early days of the internet and it was strange and new for many of the participants.) After the opening induction they did not meet – all communication was via the Forum software. This was also true of the international faculty – I worked from my home office in Brighton, England and others worked from where they were.

I had a number of groups to work with on a course on leadership. Students in each group (of around six students) had to log on at least twice a week – so that at the very least you knew that they were still alive and well even if they did little. (All communication was asynchronous and had to be via the Forum - no phone calls; no chat.) Given the objective of cross-cultural learning via elearning I made one rule for passing the course and that was that people should log on regularly (twice a week); if they did this they would pass. The grade would be a separate issue.

Other faculty members used the online environment to create a content curriculum that participants went through over the period that the course ran. I worked differently. I sent out at the start a piece about the nature of knowledge, identifying three distinct modes based on the use of personal pronouns.

- First person knowledge. This is what I know – what the individual knows.

- Second person knowledge. This is what you know – it could be an individual or a group i.e. it could be singular or plural

- Third person knowledge. This is the world of the text book and the disconnected knowledge domain. What do they know; what does he know; what does she know? It is also ‘it’ oriented – detached and often labelled ‘objective’.

(The formulation of this typology started with my PhD research (Cunningham, 1984) and is something I have developed and tested extensively since.)

I offered a reading list to cover third person knowledge and suggested that part of the process of the course would be how they could integrate these three knowledge domains. They each came with individual experiences of leadership – the first person area. They could explore the second person area via the Forum – and they could use the Forum to work on an integrative model. Such an integration was carried out by each person so there was not one model. Rather the interaction in the forum provided a basis for each person to test the way they were bringing together the different knowledge domains.

Traditional university education in this area has been based on the faculty presenting the abstract models of theorists and then expecting learners to absorb and implement these. However, where the learner has their own model, that is not in keeping with the professor’s, the personal one tends to be implemented by the learner not what is taught in the lecture hall. Argyris (1976) has researched and written extensively on this problem in relation to organisations and specifically how leadership learning can be ineffective because leaders may have an ‘espoused theory’ that does match their ‘theory in use’.

Prior to going online I had, in the face-to-face meeting, introduced them to the Self Managed Learning methodology – and two specific features of this. Firstly there was the use of a learning group where individuals could work together to support each other’s learning. Secondly was the use of a learning contract whereby the individual negotiated their own learning goals with their group and agreed, with the group, what they would do to carry them out.

When it came to the online working I was then able to ask students to start by negotiating with the group via the Forum what they wanted to learn and how that would be assessed. This had to be in the area of leadership but could otherwise be anything they wanted. Some senior managers worked on their own leadership and used theory and research to explore how they could understand how they led. Some used 360 degree feedback as a good example of taking criteria from theory (third person knowledge) and then providing their perspective on themselves (first person) and the perspectives of others at work (second person). They shared this online getting other second and third person perspectives. It also threw up interesting cross-cultural dimensions as groups had participants from the USA, Australia, Japan, Europe and Africa. And all this was done online through regular posts in the Forum group.

One example of the cross-cultural dimension was the challenge to the US-centric participants who often started with an assumption of the universal value of theories developed through purely US research. A trainer working with African managers was one who was articulate about the demands of the African context and that even there he identified cultural differences as he was asked to run workshops in a variety of countries.

The Dynamic Forum software gave participants the chance to discuss their own work and develop a rigour in their thinking through the interactions with others. Their learning was also much more coherent and integrated than if there had been an imposed curriculum that provided purely detached (third person) knowledge. For participants their original personal theories were developed and made more sophisticated through the integration of the three knowledge modes.

One participant was involved in a choir and decided to draft a book on how to lead a choir (she had not found a book on this subject in her searches). Although others in the group had no experience of singing in a formal choir they were able to engage with her on what she was writing. There was much mutual learning as others had to ponder on the applicability of many supposedly universal leadership theories via considering and commenting on her work.

A model identifying what is needed to create an effective elearning programme – using the Master’s degree as an exemplar

The MA programme exemplifies what I have discovered in other developmental programmes. I will apply the following model to elearning using this example. The model comes from extensive research, summarised in Cunningham, 1999. The initial basis for the model was from my PhD research (Cunningham, 1984) and the model was then tested in the ensuing years. The evidence from this research is that there are four basic roles that development professionals need to carry out. Ideally a person should be highly capable in all the domains indicated but often a professional team can be created that combines different capabilities so that all angles are covered.

Four Roles Model – Figure 2

The four leaves of the clover (see diagram) are broadly as follows:

- Theory. Effective practitioners are able to articulate the theory that is the basis of their professional activities. In the context of the MA we were clear about specific learning theories that underpinned what we set out to do. Some have been indicated above, such as the role of a process curriculum. Our theory about the future nature of business had an impact. Also in my course I was working from a theory of self managed learning and why that should be the basis of the course.

A factor in the theory area is the extent to which a professional person might create totally new theory (rare); modify existing theory or articulate theoretical propositions and models. At the very least we would expect an articulation of theory as a way of being open with colleagues and with learners. In teams the discussion and clarification of theory is an important factor that can be omitted as people in the team may just assume others have the same theoretical basis as themselves.

In the above I have not indicated how theory arrives and the interplay of theory and practice. Clearly professionals may modify theoretical assumptions as they experience new information from practice. And the three factor typology of knowledge arenas (outlined above) has its role here.

- There are two parts to designing:

- Macro designing is about having the strategic capability to design total processes. The requirements here are to think strategically and to implement theory in practical ways. In the MA there was a clear basis to the macro design of how to use the internet and the associated software. We had to consider the whole programme and the interplay of the various factors in the design. This included the decision to have a three day start up event followed by solely asynchronous online contact. The choice of Alta Vista was similarly part of the macro design. The decision to use international faculty was an important design choice along with the way the faculty would work together. As with all design decisions there are constraints to be accommodated. In this case there were accreditation regulations and California state laws to be adhered to.

- Micro designing is about creating specific processes such as the way the Forum was used. This also included the design of the three day start up as it was crucial to kick the programme off in the right way. Aspects of the process were the ways that the logging in would be organised and how participants would access material to assist in their learning. Constraints in this area included resourcing factors (annual budgets have to be met) and again state laws. In the latter case I was not able to implement my preferred option for each group to work out what grade each person should have, based on consensus decision making. My normal practice to do this was circumvented by California law that prohibited the publication of grades.

- Here again the role can be divided in to two:

- Leading the programme was important and how faculty provided this leadership function was vital. This also linked to aspects such as marketing and recruitment – the need to get an international mix was important as the programme could not work without it. The capabilities required in the team were at one level similar to any other team. However the dimension of the academic environment added a layer of complexity. An example was the division in roles between academics and administrators.

- Administering a programme is also crucial. Budgets have to be managed, systems created and managed, emails answered and so on. The librarian was crucial in signposting material via the online environment. Also those with the role of administrator for the groups had to be on the ball at all times to make it work. Efficient administration of the online environment was crucial as we were working with busy senior managers as participants. The occasional crashes were a problem, when mutual contact was impossible. When the system was working it was essential for each faculty member to be highly organised in responding to what people posted.

- Interacting with learners is often the most visible part of developmental activity. I will comment more on this below as this dimension raises some specific issues for educational professionals.

Note that the four leaves or segments interact and overlap. Also they need to be brought together in a harmonious whole. It’s no use getting three out of the four right – all four have to work together. All are necessary and sufficient to make an elearning programme work.

The Interactive Role in eLearning

Ideally learning needs to start with what I have called the ‘P MODE’. P stands for:

- PERSONS – we need to understand the person if we are to assist their learning. Each person is different and they have different needs.

- PATTERNS – each person will have patterns of behaviour and of thinking

- PROCESSES – each person has their own processes of working and living

- PROBLEMS – one way of thinking of learning is as a solution to a problem. For example if you can’t speak French and you need to then you have a problem and the solution is to learn French. Or if you need to write well to progress in life and work then the solution is to learn to write well. And so on.

Note that in the latter example, problems come before solutions. In our approach, the P MODE comes before the S MODE

The S MODE stands for:

- SOLUTIONS – to respond to the person and their problems there may be a need to look for solutions

- SUBJECTS – subject knowledge may help to meet the ‘P’ needs

- SKILLS – may be needed to progress

- SPECIALISATIONS – may contribute

as may

- SYSTEMS – such as IT systems.

Elearning too often starts with ‘S’ – people have imposed on them Subject knowledge and Solutions to Problems that they have not yet formulated. Or the Solution distorts the way the Problem is tackled. In the MA it was important to have the three day induction event so that I could understand the students with whom I was working. Then when we were online I was in the best place to offer help – this could be Subject knowledge, possible Solutions to the problems that they were dealing with, ideas about Skill development and so on.

In thinking of the role of staff, we find that we start in the ‘P’ Mode. Once learners are clearer about what they want to learn and how they want to learn it they may need to draw on expertise in the ‘S’ mode. It is here that more Static elearning comes in. In the past teachers were seen as the main source of ‘S’ learning. Now we have the vast array of material on the internet and the use of teachers changes. However we find that learners often welcome support, especially where they can get help to avoid wasting time on irrelevant websites.

Self Managed Learning College as an example of elearning practice with young people

It’s now time to come up to date and skip from the mid-1990s to the present day. Also here I want to shift the focus from adult learning to work with young people. The case I will mention is of Self Managed Learning College. The College works with 9-17 year olds who have rejected school or been rejected by school. Students decide for themselves:

- What they learn

- When they learn

- Where they learn

- How they learn

- Why they learn.

The College is located on the outskirts of Brighton and Hove on the south coast of England. When students newly arrive they are helped to plan an overall strategy for learning (see www.college.selfmanagedlearning.org for more on this and other aspects of the programme not covered here). After that they are assisted to write their own individual timetables each Monday morning and they review their learning on Friday.

The programme clearly fits in the SE corner of the Coomey and Stephenson (2001) model. Students choose the extent that they use computers, smartphones and other technology. Unlike local schools there are no controls on what students can access online – apart from a control on the use of chat rooms. There is a rule (agreed by students) that a maximum of 30 minutes per morning ought to be for computer games and Facebook. This is not kept to strictly but students are challenged by peers if they abuse computer or smartphone use.

We are able to demonstrate how we can integrate digital technology with other learning modes – and we make a Self Managed Learning mode work. We can return here to the distinction between Dynamic and Static approaches. Dynamic approaches are where students create their own material via Facebook, self-created games, creative designs via Photoshop, etc. Dynamic approaches are driven by the process not the content. Students create their own content.

Static approaches are where students access pre-created content such as the use of the Kahn Academy for learning mathematics. For the student to use a Static approach they will first of all determine what they want to learn and how best to do it. They are then in the position to get assistance from staff (if needed) to access an appropriate website or whatever. Hence the Static approach is not used as a result of a prescribed curriculum (there is no content based curriculum) but rather as part of a more Dynamic learning process.

Some commentators might describe our approach as ‘blended learning’ as it is not based solely on elearning. We would not use such terminology. For one thing much blended learning is generally about using elearning with classroom learning – and is clearly teacher controlled. We have no classrooms. Students use a wide range of learning approaches that suit their needs. A better formulation is within Luckin, 2010. She uses the term ‘Ecology of Resources’. In the research that Rose Luckin and Wilma Clarke (of the Institute of Education, University of London) conducted with our students they initially worked to identify the range of learning modes available to students and then studied how these were used. The case explored in Luckin, 2010, is of a trip to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.(2) The researchers showed how a range of learning modes could be integrated based on the ‘Ecology of Resources’ model – explored more fully in Luckin’s book.

Mentioning trips is a good example of how students would use the online environment. In the college we meet every morning at 09.00 to sort out any issues and to plan ahead. Students might come up with the idea of a visit, say to a museum or art gallery. Those students who are most keen on the trip take on the task of organising it. The first stage tends to be doing an online search to assess the feasibility of a trip. After that the website of a selected museum would be searched to find the best time to go, how to maximise the time at the museum and so on. Note that this is all student driven and that they learn a whole range of skills in doing this planning – not just effective searching (they are usually already good at this) but how to cost, how to get agreement in the learning community about what to do, how to schedule, how to organise transport, etc.

While in the above example students would typically use a laptop, increasingly much learning is via smartphone. Ofcom (2012) report that, in the UK, four in 10 smartphone users say that their phone is more important than any other device for accessing the internet. As the Ofcom report shows, smartphones are essentially handheld computers that just happen to be able to make voice calls. This is what we observe. Unlike most local schools, which ban the use of smartphones in the classroom, we encourage students to use them. Examples might be useful here.

Clive is a fifteen year old who is keen to run his own business at some time in the future. He is using various modes to further his possible career including formal learning about business. Another student, David, had identified an app on his phone that allows you to pretend to have £25,000 to invest in the stock market. You can then make pretend investments and see, in real time, how they are doing on the stock market. Having shared this with Clive, the two of them started a competition to see how well their investments were working out using this app. I challenged Clive as to how much he knew about the companies in which he was investing. As I suspected he was largely guessing. I then showed him that he could do more effective online searches about companies including going onto the Companies House site and downloading company reports. This led him into having to be more knowledgeable about how to analyse company accounts (an area he had started to cover in his formal learning).

Margaret Mead was once challenged about her support for more child-friendly modes. Her adult critics commented along the lines of: ‘We were young once so we know what children need.’ Her response was ‘Yes you were young once but you have never been young in the world that young people now are young in.’ This response is even more relevant today. While there is controversy as to the extent that children’s brains are being re-wired due to technology there is no doubt that the availability of advanced technology and of the internet creates a whole new world for young people. Our students have grown up in this world and learning modes need to respond to it.

Another example

Through collaboration with the University of Sussex two groups of Master’s degree students in the Informatics Department have worked with two of our 11year-olds. Each of the 11 year-olds has come up with an idea of something that they would like to develop and they have been prepared to learn computer programming in order to achieve what they want to do. For instance an 11 year-old boy is interested in aircraft and has already developed his knowledge and skills in this area. He had used a simulator and wanted to develop something along those lines. One of the Master’s degree groups worked with him to understand what he wanted and then went away to produce material so that he could program a game featuring aircraft. This is an example of how our students can drive the learning process.

The existence of the online environment is now part of everyday life. Whether schools and universities like it or not young people are increasingly managing their own learning via the internet. Unfortunately the tendency in educational institutions is to try to continue with control mechanisms that they are used to. For example no local schools where I live allow access to YouTube yet our students use it all the time – to learn guitar chords or how to tune the drum kit. One student (a good singer) has recorded numerous songs that are out on YouTube and gained great feedback. Her confidence has grown enormously in being able to access a world-wide audience for her music. In school she would not be allowed to do this.

Of course there are undesirable materials out there on the internet. By keeping our College small and working as a community to monitor usage we generally have no problems. Many young people with computers in their own bedrooms can, in any case, access quite appalling material without their parents or teachers knowing. The main issue for adults to face is that the internet exists, it has its downsides, but it is here to stay. We have to help young people to learn how to use it sensibly not try to keep it under control. Because the controls will not work anyway.

Our approach has been to operate as a learning community which we keep small and where the community as a whole polices any rule-breaking. The community meets every morning to address any issues that may come up. The only time we had an issue with computer use was three years ago when a new student went on a dubious chat site. After that incident the community agreed to block chat sites. This incident is the only one we have had in 12 years so we know that creating a trusting environment with simple rules and collective policing works. However I have seen students in a local school accessing appallingly violent images, even though the school has ferocious controls that block many sites.

A development which we have responded to is BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) (Dunnett, 2012). This is growing in the business world. In our context it means that students bring in their own laptops (smartphones have been mentioned already). Clearly we have to trust that parents will put in any controls that they want. So far we have had no problems and students are able to work on and take away work on their own kit – to their advantage.

Digital Education Brighton as a collaborative project

Digital Education Brighton is another example of a current development. It was set up in the summer of 2011 to bring together local digital companies and schools and others (such as ourselves) involved in education. The group works on the basis of real projects delivered via self-selected project groups. An example of a project is one that came about through contact to the group from the Cherokee Nation in North America. Their young people wanted to interact online with school students in Brighton. This was set up involving history and geography teachers in schools. The interactive mode has allowed for mutual learning between young people in the Cherokee Nation and Brighton young people. Note that it is not being run in school IT/computing departments but through teachers in relevant subject areas and allows for live learning.

A formal launch of the project occurred on 19 September 2012 in Brighton, although work between the two Cherokee schools and the two Brighton schools had already started. More is on the Digital Education Brighton site e.g. at http://digitaleducationbrighton.org.uk/?p=276. However here is flavour of one person’s response to the launch

“Just to give you a quick update on last night's launch event. I thought it was great. There were about 60 school students from Blatchington Mill and Cardinal Newman [the Brighton schools] creating a visual and verbal mash up of Cherokee culture and their own. I loved the audio mix of Cherokee Nation lullabies and the Brighton kids talking (quite prosaically) about what they would take to the afterlife ("I'd take One Direction" was my favourite). The school students creating the cleansing flames of the afterlife through dance and that then being superimposed on Cherokee iconography was also really cool.

It was also great to hear the Heads of the two schools talking afterwards to us all about how excited they were to be part of the project. And the welcome video from Cherokee people and teachers was also strangely moving. As one of the Cherokee schools described it, a digital pow-wow.”

A brief conclusion

What I have wanted to do is to show examples of how a real learner-centred approach can work. What I have tried to show in this chapter is that there can be a different way of thinking. The chapter contains well-researched models that can inform practice as well as examples of practical applications. None of this is complex – it just requires the mindset to go with the approach.

I suggested an important distinction between Dynamic and Static approaches to elearning. Later in the chapter I showed how we need to have a basis in the Dynamic so that Static modes can be used effectively. I showed how a Master’s degree can work using Self Managed Learning as a basic methodology and I used the experience of this programme to flesh out a model for professional practice. I outlined how a programme for young people can utilise an integrated self managing approach to the application of elearning. The final example was of a cross-cultural project involving young school students in England and in the Cherokee nation.

My aim in showing a variety of examples linked to some general models is to show that the theoretical and empirical basis of the models makes application viable and practical. I have produced what I label process models which are content free. The use of process models allows practitioners to insert their own factors and variables into the models. For instance the Four Roles model of professional practice was exemplified in this chapter by reference to experience in the MA programme. However in creating any elearning programme the factors involved in that can be inserted into the model and it can be used, for instance, to assess the capabilities in a development team. Are all aspects covered within the team? And is there coherence and integration of the factors? For instance if the programme is based on a particular theoretical framework is the design consonant with that? And will the interactions with learners exemplify the application of the theory?

Endnotes

- The distinction between strategy and tactics is based on ideas from warfare. Strategy is about winning the war; tactics are about winning battles. You can win battles but lose the war, so strategy defines the overall objective. In learning, strategy is based on the overall needs of the learner and tactics can cover ways of meeting the learning strategy; tactics are at a more functional level.

In some of the examples in this chapter I have tried to show that a strategic approach is important and is not based on just lots of tactical or functional learning. For instance learning random subjects without thought of integrating these is an example of tactical learning without strategic coherence. In all this I am making a link to the notion of business strategy as it has become articulated over the last few decades. Strategy is generally about the big picture and the longest time horizon for action. Tactics are generally dictated by the annual budget in many companies. In education tactics can be dictated by a timetable or schedule of activity. If it has a strategic basis – all well and good. But often such short term scheduling reduces strategic coherence.

These distinctions are explored more in Cunningham, 1999.

- Luckin’s (2010) book has a very detailed analysis of the use of a learner-centred approach to the use of technology and other learning modes. The research related to our programme is from page 135 but the reader would be advised to study the earlier parts of the book to understand the models that she uses. Please note that at the stage of her research we worked under the label of the South Downs Learning Centre and only changed our name in 2011.

References

ARGYRIS, C. (1976) Increasing leadership effectiveness, New York: Wiley-Interscience.

COOMEY, M. & STEPHENSON, J (2001) ‘It’s all about Dialogue, Involvement, Support and Control’ in Stephenson, J. (ed.) Teaching and Learning Online, London: Kogan Page.

CUNNINGHAM, I. (1984) Teaching styles in learner-centred management development, PhD thesis, Lancaster: Lancaster University.

CUNNINGHAM, I. (1999) The Wisdom of Strategic Learning. 2nd ed., Aldershot, Hants: Gower.

CUNNINGHAM, I., BENNETT, B. & DAWES, G. (Eds.) (2000) Self Managed Learning in Action, Aldershot, Hants: Gower.

DUNNETT, R. (2012) ‘Bring your own device’ in The Director, May, pages 55-59.

HOFSTEDE, G., (2001) Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd Edition, Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications,

JACKSON, P.W. (1968) Life in Classrooms, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

KOESTLER, A. (1964) The Act of Creation, London: Hutchinson

LUCKIN, R. (2010) Re-designing Learning Contexts – Technology-rich, learner-centred ecologies, London: Routledge.

O’CONNELL, D. ( 1994) Implementing Computer Supported Cooperative Learning, London: Kogan Page.

OFCOM. (2012) The Communications Market Report, London: Ofcom.

SNYDER, B.R. (1970) The Hidden Curriculum. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

TROMPENAARS, F. & HAMPDEN-TURNER, C. (1997) Riding The Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business , New York: McGraw-Hill

VALLANCE, E. (1983) ‘Hiding the Hidden Curriculum: An Interpretation of the Language of Justification in Nineteenth-Century Educational Reform’ in Giroux, H. and Purpel, D. (eds.) The Hidden Curriculum and Moral Education, Berkeley California: McCutcheon

Ian Cunningham, 2012 ian@smlcollege.org.uk